The hydrogen bomb legacy

Ron Watson was just 17 when he experienced his first nuclear weapon blast.

A British soldier from Cambridgeshire, he had completed his training in the summer of 1957 before departing on Boxing Day on a fateful tour with the Royal Engineers.

After the excitement of leaving on a specially chartered train carrying thousands of men and then sailing across the oceans, he was wholly unprepared for what awaited him during his posting in the tropics.

The 79-year-old explained that the first thing to strike him was an unbelievably bright light.

“I had my back to the explosion,” he said.

“My eyes closed with my hands covering them.

“I clearly saw the bones in my hand, just like you see them if you look at the results of an X-ray.”

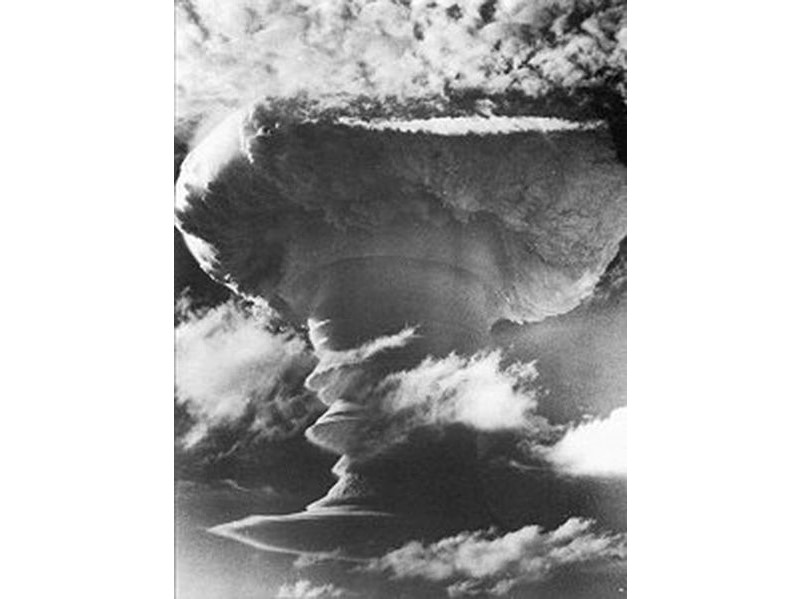

Grapple H-bomb tests

It was 28 April 1958 and Watson had witnessed the British Army’s Operation Grapple YH-bomb test on Kiritimati – better known as Christmas Island, a stunning coral atoll with crystal clear waters and blue skies.

For ordinary Brits, Kiritimati was far away, out of sight and out of mind, except when the media reported successful tests with pride.

While South Pacific islands like Kiritimati were often described as a pristine uninhabitable wildernesses by the military officers who chose them, this was often far from the truth.

Local people were forced from their homes at best or, at worst, were left in place potentially to be exposed to ionising radiation.

The long-term impact on their lives and families has been largely ignored, as has that on the local people who lived, and still live, across the islands where nuclear testing occurred.

Intertwined lives of the survivors

For the last few years, Dr Becky Alexis-Martin, lecturer in Political and Cultural Geographies at Manchester Metropolitan, has been researching the intertwined lives of both British nuclear test veterans and Kiritimati communities as they continue to try to make sense of their experiences.

Teeua Tetua was just three when she was blindfolded with a rough cloth by her mother as they braced themselves for the Grapple Y explosion.

She was very young but still recalls being frightened in her mother’s arms during the deafening blast.

Now 64 and chairwoman of the Association of Nuclear Victims in Kiritimati, her home is strung with cowrie shells collected from the beach, and serves as a children’s nursery.

Teeua said: “There has been no compensation. I worry about cancer and other effects to health – this is why I campaign.”

Philomena Lawrence, a Kiritimati islander who now lives in the UK, recalled how villagers were taken to a boat to watch a Disney film to distract them during one test and how they were told to gather on a tennis court covered by a tarpaulin for another.

“The locals were terrified,” she said.

She described how she knew of two women who were born with birth defects after the tests, adding: “There was little understanding of harmful effects.”

Frightened and uncomfortable

Dr Alexis-Martin spoke to a further 14 Kiritimati islanders who all remember being frightened and uncomfortable and described the tests in terms of confusing events, crowds, megaphone countdowns and deafening noises.

Dr Alexis-Martin said: “In the aftermath of the explosions, diet staples coconut and fish caused food poisoning and while the islanders continued to eat andb ecome unwell, the servicemen were ordered not to consume the local foods because of contamination concerns.”

She explained that veterans, meanwhile, spoke of living intents despite the intense heat and mosquitos and of how some men developed ringworm and swellings.

“Their descriptions of minimal protective clothing, line-up drills, and radiation sampling provide a vivid narrative of the realities of their work,” she said.

“There was also limited interaction between servicemen and islanders.”

Segregation and sunstroke

Veteran Robert McCann, 80, from Hampshire, said: “I never mixed with locals the first time I was there. I saw them, but only from a distance.”

The segregation meant many of the young servicemen had no opportunity to get to know islanders, which shielded them from learning of the impacts of the tests on local people.

Although the soldiers believe that it was the nuclear weapons that posed the greatest risk, their work presented many other hazards, including sunburn, sunstroke, accidents, exposure to carcinogenic DDT, poor sanitation, dysentery and inadequate rations.

Many of the British servicemen involved in the operation – and their families – were left scarred for life by their experience on the island.

They were traumatised by what they had seen and by the culture of secrecy that surrounded their work.

And once home, soldiers were damaged by the apathy they received from the government of the time.

Military secrecy

Dr Alexis-Martin said: “Military secrecy has meant there has been no specific long-term health study for nuclear test veterans and no similar research on the Kiritimati community.“

The way that risks were managed has affected the veteran community’s understanding of their experiences.

Despite assurances that the nuclear tests posed little risk of radiation exposure, they have had diverse repercussions and the true costs of the tests are only just beginning to emerge.

“This is why I set out to explore the lives of nuclear test veterans, and their children and grandchildren. I discovered challenges of specialised aged veteran care, evidence of heightened perception of risk of radiation effects and impacts on wellbeing and mental health.”

Concerns were raised by servicemen’s descendants about reproductive risks and some daughters of nuclear test veterans had chosen not to have children due to their heritage.

Susan Musselwhite’s father was a navy diver on board HMS Narvik, a control ship for the Montebello Island and Grapple nuclear tests.

The 39-year-old, from Devon, suffers from numerous conditions, including chronic migraines, thyroid issues, nerve damage, bowel and bladder issues and Grave’s disease and depression.

She also had fertility and other women’s health issues from an early age.

She said: “I truly believe that I have these health issuesbecause my father was at the nuclear weapon tests.”

Dr Alexis-Martin said: “The stories of the islanders and veterans, and their descendants, demonstrate the need for recognition and reparation for the injustices that the British state perpetuated against both veterans and Kiritimati communities during the Cold War.

“Both communities have soughtsuch recognition, with limited success, and yet the voices of those affected are becoming louder.”

FACT BOX:

- Kiritmati is one of 33 low-lying islands that constitute the nation state of Kiribati in the Pacific Ocean

- About 20,000 British servicemen, 524 New Zealand soldiers and 300 Fijian soldiers were deployed from 1956 to 1962

- Between May 1957 and September 1958, the British government tested nine thermonuclear weapons on Kiritimati under the name Operation Grapple

- In 1962, the UK cooperated with the US on Operation Dominic, undertaking a further 31 detonations

- British Nuclear Test Veterans Association is campaigning for medals for the nuclear test veterans and its work has expanded to include support for the people of Kiritimati who have been affected by the tests

- UN Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty has outlawed all nuclear weapon testing since 1996

- Kiritimati is now part of the South Pacific Nuclear-Free Zone