The art of storytelling

Spinning a yarn, painting a picture, telling a tale – the art of storytelling has been around for as long as humans have roamed the planet.

It’s in our nature to share the fantastic and the magical, to recall, to create new ideas. As an old proverb goes, those who tell stories rule the world.

Storytelling even predates the earliest forms of writing, with our ancestors sharing stories through the spoken word or gestures. These tales were passed down from generation to generation, folklores and fables recalling battles of old or the mysterious ways in which the gods work.

The Chauvet Cave in southern France contains some of the world’s best preserved cave drawings dating back 30,000 years, depicting the stories of early humans. One of the earliest written stories is the poem Epic of Gilgamesh, dating from 1800BC, a story of kings and gods, of adventure and the quest for eternal life.

Tales as old as time.

These ancient stories are part of a rich lineage of storytelling that became ever more sophisticated as the years passed. Think William Shakespeare and today’s silver screen blockbusters.

And while the media may have changed – from cave drawings to computer games – the idea remains much the same: to inform, to provoke, to inspire and to entertain.

This continues today with our storytellers gracing cinema screens, penning best-selling books or even sharing stories on social media. In the UK, arguably no modern storyteller has had as much impact in recent years as Oscar-winning film director Danny Boyle.

From the stage to Hollywood, Greater Manchester-born Boyle is a household name with a hit parade of films dating back to the 1980s: Trainspotting, The Beach, 28 Days Later, Slumdog Millionaire, 127 Hours. A cursory glance on the internet tells you all you need to know, with Hollywood glitterati Leonardo DiCaprio, Kate Winslet, Ewan McGregor and Michael Fassbender just some of the actors to have worked with Boyle.

And that’s not forgetting the critically acclaimed opening ceremony to the 2012 London Olympics – as grand a stage as you will find – in which Boyle captivatingly told the story of Britain. A story in which the Queen, next to James Bond, memorably ‘parachuted’ from a helicopter into the Olympic stadium.

Now, the esteemed director is turning his attention to Manchester Metropolitan and its own rich history of storytelling.

A new type of creative education is coming, a new way to create for the 21st century: the School of Digital Arts (SODA).

SODA, a £35m investment by Manchester Metropolitan and the Greater Manchester Combined Authority, will house more than 1,000 students annually and bring together expertise in film, animation, UX design, immersive technologies, photography, games design, AI and more, often working on live projects with industry partners.

First unveiled as a concept in February 2017, SODA will open in 2021 and building work on its new home is now underway. Boyle is co-chair of its industry advisory group ready to shape the next generation of storytellers.

Met Magazine caught up with Boyle ahead of the first SODA industry event talk. The inaugural talk was delivered by Boyle at HOME, an international contemporary art, theatre and film centre just a stone’s throw from the University.

His talk, Will Robots Love Jesus?, took a provocative look at the growth of technology, which was followed by a panel Q&A (pictured above) that included fellow SODA industry advisory group co-chair Nicola Shindler, Executive Producer of RED Production Company and CEO of StudioCanal UK.

“I’m the last person you should ask about the future of storytelling,” he said.

“Because actually I’ve had quite a successful go at telling stories up until recently. I would tend to recommend that path because it worked for me, and why would I want to consider anything else or think about anything else?”

He added: “When I heard about SODA, I thought what a wonderful thing. But I’m not a future storyteller, that’s what the School of Digital Arts is about – about creating the space where future storytellers can begin to find their footing.

“It’s something that I was very excited to be offered because it allowed me to at last feel I could do something useful with all the benefits that I’ve taken and used quite selfishly.”

Boyle has already dipped his toe into the water, working with students ahead of the inaugural talk, which is part of SODA’s Future of Storytelling industry event series. He worked with students in the University’s Manchester School of Art to provide thought-provoking ideas for them to create digital art that was screened during his talk.

He said: “It was a chance to actually get them to visually contribute to it and some of the images that they created were running in the background of the speech and hopefully cheering the place up rather than me just droning on.

“That’s the thing about future storytelling. You’ve just got to kind of trust it – leap and the net will appear, as they say.”

But what about Boyle’s journey, what shaped the young lad from Radcliffe, Bury, a town in the north of Greater Manchester?

Born in 1956, Boyle and his family lived in a working class district, growing up with two sisters, one of who is Boyle’s twin. From a young age, he gravitated towards the creative, the art of the story, and took an interest in drama, later studying English and Drama at Bangor University in North Wales.

Boyle’s early career saw him honing his talents on the stage and in TV, serving as the artistic director at the Royal Court Theatre Upstairs in the early 1980s and later as deputy director at the Royal Court Theatre. He also directed five productions for the Royal Shakespeare Company.

Boyle then made the move across to TV and directed various shows, including episodes of Inspector Morse and the BBC Two series Mr Wroe’s Virgins.

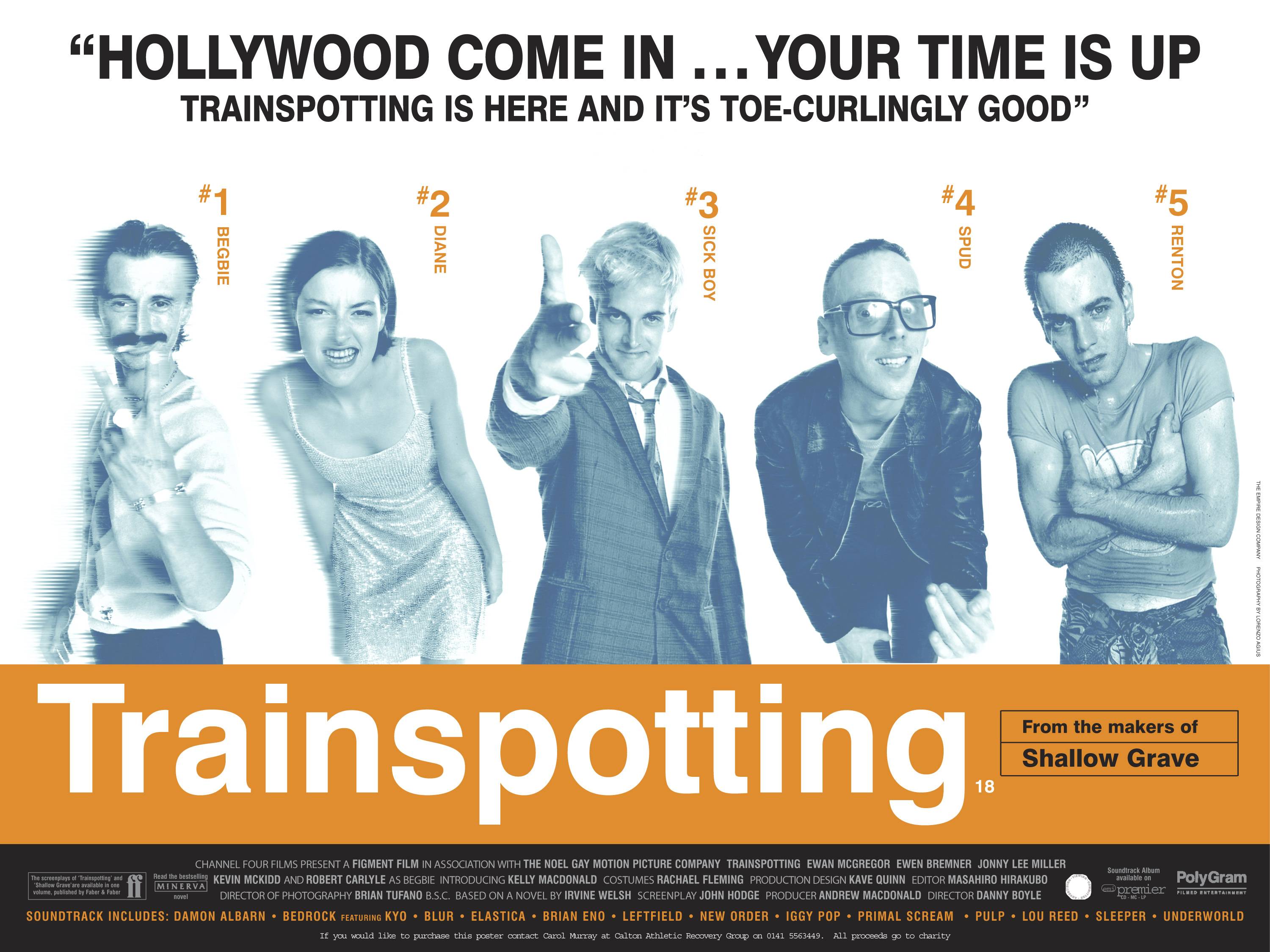

By the early 1990s, he was beginning to make waves in the film industry with black comedy Shallow Grave drawing rave reviews, followed by the era-defining Trainspotting, the story of a group of drug addicts in Edinburgh eking out an existence. The film, and its soundtrack, is indelibly etched in the cultural consciousness of the country, just as synonymous with the 1990s as Oasis or Tony Blair.

At the start of his career, with 1980s Manchester offering little for an up-and-coming director such as himself, Boyle moved to London to realise his potential. He recognises Manchester back then was a far cry from the city’s vibrant cultural scene today.

“I left and went to London before the major shift in music happened, which saved the city, really, and rebirthed it, recrystallised the city,” said Boyle.

“The attitudes haven’t changed, nothing will eradicate that. But the new initiatives are clearly a benefit to everyone.

“When I was a teenager, or an age where you’re thinking about going to college, there was very little: you had to go to Hulme, to the Aaben cinema, to watch European movies of any kind.

“I think it’s an opportunity with the investment that’s going on and the shaping of the city. There is an opportunity for Manchester to really establish itself as a major cultural hub, a European hub. I know we’re in crisis with our relationship with Europe at the moment, but I see it on that kind of scale not as an alternative to London, but as somewhere as a European hub.

“There’s enough tradition here that it’s a good starting off place for a new emphasis on culture.”

It is the love of music and the various musical scenes that grew across the UK that Boyle cites as a major inspiration in his life. If you have watched his films, you will know the central role music plays, from the iconic opening scene in Trainspotting soundtracked by Iggy Pop’s Lust for Life, to the new film Yesterday, which is centred around the music of The Beatles.

“I’ve always been – as so many people from Manchester and from many other cities have – saved by music,” said Boyle.

“I was very fortunate that, unlike in cinema, my actual artistic lifespan has included two huge decisive forces in music.

“Punk rock. I was 20 when punk rock hit. So that was my era and then 15 years later, house music and dance music.”

He added: “It’s one of the things that restricts me now. Previously I used music in films in a way that was effortless. I didn’t even think about it and I used to do interviews where people would be impressed and I just could never really understand what they were talking about because you just kind of used it.

“But now I understand because I no longer have that instant access to it, that effortless knowledge which you get when it’s part of your breathing life.”

Like a rock rolling down a hill, Boyle’s directing career only picked up more pace. From the runaway success of his 1990s hits to the stratospheric success of the 2000s.

After the critical and commercial successes, Boyle then reached the pinnacle of the film industry and scooped a haul of Academy Awards – the Oscars – for British film Slumdog Millionaire. The film won eight Oscars including one for Boyle as best director, to add to the BAFTA and Golden Globe awards in the same category.

A couple of years later he came close again when nominated for best motion picture and best writing for 127 hours, a fascinating true story of a climber’s life-and-death predicament after becoming literally stuck between a rock and a hard place.

Then of course, with the world’s eyes upon Britain, the 2012 London Olympics was launched with Boyle’s opening ceremony that attracted an estimated 900 million worldwide audience. His fantastical show covered everything from the industrial revolution to the NHS, to literary heritage, music and culture, threaded throughout with humour.

It was praised for – yes, you guessed it – its vibrant storytelling.

But what of the future, what does it hold for storytelling? Where does Boyle think it has been and where does he think it is going?

While many may think special effects have revolutionised films – techniques used with aplomb by Boyle in his films such as sci-fi space drama Sunshine – he isn’t sure this has been the major revolution.

Digital filming promised a breakthrough too, technology Boyle was at the forefront in adopting. He made one of the first widely distributed digitally released films, 28 Days Later, which was both shot and released digitally.

As an interesting sidenote, Boyle explains that recording on digital camera as opposed to physical film was done on purpose for 28 Days Later. He used what was effectively a consumer camera to shoot the film to mimic what would happen to the film’s main protagonist if the scenario were real – ie a man who awakes in a post-apocalyptic UK – in that someone could find a consumer camera and start filming to document what they see in the ravaged wasteland.

“There was always this feeling around that time that digital would let us throw off the shackles of the restrictive palette that Hollywood allowed us,” said Boyle.

“I remember thinking that there’ll be so many comedies come out because you don’t need money to make a comedy in a film. In fact, you learn very quickly that the higher the production values of comedy, the less funny it is. You want to make it cheap and cheerful, really.

“I thought, well, there you go: digital consumer cameras will free so many comedy writers to come in.

“It hasn’t quite worked out like that.”

The biggest stepchange Boyle has seen was the development of animation. He said: “In my career time, there has been a wave and it’s animation. The quantum leap forward that animation made through Pixar was extraordinary.

“You knew it as soon as you saw it, bang, it was there. It took a few visionary people to believe in it and trust in it and finance it, until it did arrive.

“I think special effects to a degree, but I’m not convinced because that’s just an ongoing continuum. I don’t think it’ll be looked back as being particularly distinctive. Whereas I think the Pixar cinematic universe is a much more important stepping stone than, say, the Marvel Cinematic Universe with all its special effects.”

And then of course, there are the new kids on the block – the streaming platforms. Their seismic effect is only now being properly understood.

The modes of production, the tools at storytellers’ disposal may have become rocket charged as digital techniques became available, but TV and film’s battle for eyeballs remained essentially the same. A film was made, it went to cinemas and then maybe later onto DVD. Equally for TV, shows were developed and broadcast at the best time slots, repeated every few days or every week.

Not now. Netflix, Amazon Prime and others on the horizon, create their own content and release on their own internet-enabled platforms. No prearranged screenings, no set times, no weekly timeslots. The viewer watches what they want, when they want.

“It’s clearly changing the industry,” said Boyle. “The powerbrokers are no longer just the studios, the platforms are changing.

“The film as a single experience is hanging on a bit at the moment and only managing to hang on through big event movies. And the movies that were celebrated in the seventies, which are kind of mid-range budget movies, which tend not to be full of special effects and not full of superheroes, are being squeezed.

“Yes, you can make films very, very cheaply or very, very expensively. There’s nothing really in between because all the in-between ground has moved onto the streaming services, which at the moment are flush with money.

“That won’t last forever because more competition is beginning to enter the field. They’ll only confront it when they have to, (people are) not going to pay for ten different streaming services, that will have to be rationalised. So quite how that will work, I have no idea.

“I think it has changed the nature of storytelling. I think storytelling is endless now and is encouraged by the platform to be endless.

“People have a different relationship with it. It’s an obsessive relationship but also in a curious way, it’s kind of casual and less caring than the effort you make to go to the cinema to watch a single piece of work, which I would. That’s my kind of storytelling.”

But the future’s bright and technology affords new opportunities, according to Boyle. Stories will be told in which the viewer is no longer passive and no longer sitting idly by – you are in the story.

It is this new wave, this new generation which SODA and its students will be at the forefront of, knitting together the technical and the creative to nurture future-proof graduates. Somewhere for the new Danny Boyle to find their voice.

“I think the thing that the industry is poised for, waiting to see what happens with these future storytellers, is the use of augmented reality or virtual reality or immersive experiences,” said Boyle.

“Punchdrunk and other companies, they’re beginning to kind of create immersive experiences for people.

“They’re becoming a bit more common, a bit more mainstream. But how will they be used in storytelling, in original storytelling? I have no idea and this is what I mean about not being a future storyteller.

“I went to a thing at the Saatchi Gallery called We Live in an Ocean of Air, which is by this company Marshmallow Laser Feast. It was the most extraordinary 20 minutes of immersive experience with the glasses on and everything.

“But I couldn’t work out how to make that into a story, how to use that as a story.

“I know with the regular cameras. I know the path between a story and how to get it there and what to use to get it there.

“I had no idea how you would use this. This wrapping of people inside the medium and being able to tell the story as well, rather than being outside the medium.”

And who will be bridging this divide, making these new immersive stories work?

As Boyle said: “That’s one of the answers that will come from this new generation.”

You can listen to a special double podcast of Boyle's talk at HOME and the industry panel Q&A here.