An act in two parts

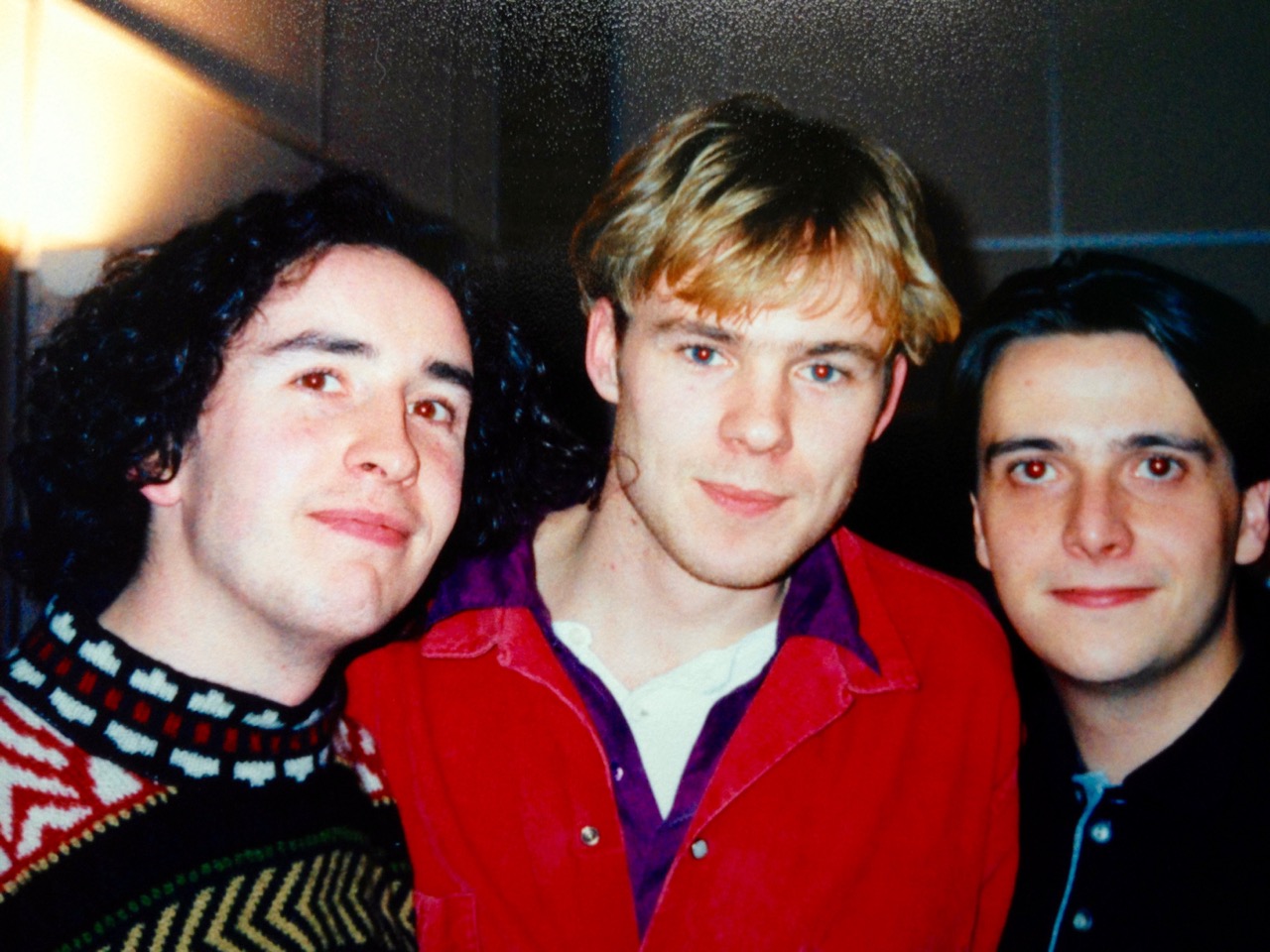

(header image: Thomas Laisne) See here for the full issue 9 of Met Magazine

The wannabe Manchester School of Theatre student knocked on the door, asked if he was in the right place, and promptly spilled his papers all over the floor.

“I just want you to relax and enjoy my audition”, he overconfidently repeated to the panel, who were more accustomed to watching polished Shakespearean soliloquies than this chaotic display.

But rather than politely show the young man to the exit, the chair of the panel said something rather surprising instead.

“We normally operate a recall system here, but we’re going to offer you a place straight away.”

For this seemingly inept audition was actually a virtuoso comic performance piece. The hapless tryout was doing an act called Duncan Thickett, a bumbling stand-up whose brazen lack of self-awareness bore early hallmarks of the character who would become one of Britain’s most enduring cultural creations – Alan Partridge.

The year was 1985 and that audacious auditionee was Steve Coogan, recounting the above in his autobiography Easily Distracted. Then a hopeful actor in his late teens with raw comic timing and an uncanny knack for impressions, Coogan’s only acting experience amounted to a regional theatre company that toured northwest schools.

Over the next three years, Coogan cut his teeth on the acting course at the then Manchester Polytechnic, all the while making his first successful forays into local stand-up, voiceover work, and even radio and television.

Such overnight success wasn’t the norm for someone still learning their craft, but it was an early indication of a rare talent that would make him one of the most recognisable faces in British entertainment.

In fact, he was hanging out with his fellow students in the Manchester School of Theatre canteen when he got a phone call from his agent with the news that would change his life forever.

In his autobiography, he recalled relaying the news to his classmates. “I’m the new voice of Spitting Image.” he said. “They looked at me, as shocked as I was: “You jammy bastard … I suppose you’ll be all right then.”

Starting out

Almost 35 years later, Coogan is more than alright. His comic performances as Partridge, first in On The Hour and The Day Today before various solo projects, have scooped him numerous BAFTAs, while Philomena, his first screenplay, was nominated for two Academy Awards. His collaboration with director Michael Winterbottom continues to bear fruit through the final series of The Trip and 2020 feature film Greed, which he returned to his native Manchester to promote.

Speaking to Met Magazine before the COVID-19 pandemic, Coogan reminisced how it all started in the city’s eclectic alternative scene of the 1980s, the period he so memorably captured in his first Winterbottom collaboration 24 Hour Party People as Factory Records impresario Tony Wilson.

His first stand-up gig was at Wilson’s famous Hacienda in 1986. “That was before Madchester, the Happy Mondays and the Stone Roses – that came at the end of my tenure.

“Everyone went around in big overcoats that they bought at second hand shops, and it was very fashionable to look to suck your cheeks in and look introverted and introspective, slightly miserable and androgynous, sort of strange. The Smiths was my soundtrack for my time in Manchester.”

Before Coogan’s time, Manchester School of Theatre already had some celebrated alumni, Julie Walters and David Threlfall among them. Others have followed in his footsteps, including Game of Thrones star John Bradley West.

The friendships and connections Coogan forged during his time at Manchester Metropolitan were career defining. “My memories of that time are very, very happy ones,” he said. In his first year, he met third-year Simon Greenall, who gave Coogan his first broadcast work on BBC Radio Manchester after overhearing his skill for impressions in the college canteen. He was memorably cast a decade later as incomprehensible Geordie handyman Michael in I’m Alan Partridge.

Two years later, Coogan met and began working with the actor John Thomson, who had just enrolled at Manchester School of Theatre and would become a regular feature in his early TV work. Their double-act won the coveted Perrier Comedy Award at the Edinburgh Fringe in 1992.

The student Coogan immersed himself in Manchester’s arts and theatre scene, working as a stagehand at the Royal Exchange Theatre, and going to see films at the Cornerhouse cinema – later Manchester School of Theatre’s temporary home.

But Coogan said, while there was no shortage of emerging comic talent, “there was no alternative comedy scene in Manchester.” He and his comedy cohort mixed with musicians and poets, and Coogan found himself warming up for indie bands.

“There was a place called the greenroom on Whitworth Street where I started performing towards the end of the 80s. I met Henry Normal, Caroline Aherne performing with John Thomson, Dave Gorman, the late Brian Glancy, who Elbow wrote an album about called Seldom Seen Kid. I used to see Lemn Sissay a lot.

“That little arty scene that grew up around the greenroom was where I honed my craft, because that was the only real alternative venue, but it wasn’t even for comedy.

“There used to be buskers nights where guitarists like ‘Guitar George’ George Borowski would perform, with other poets, miscellaneous musicians, performers, a motley crew of different people who didn’t fit into the normal way of things.”

His experiences at Manchester Metropolitan – or specifically of observing drinkers in the Parrs Wood pub near the School of Theatre’s then Didsbury base – also inspired the creation of his first breakthrough comic character act, Paul Calf.

There was a place called the greenroom on Whitworth Street where I started performing towards the end of the 80s. I met Henry Normal, Caroline Aherne performing with John Thomson, Dave Gorman, the late Brian Glancy, who Elbow wrote an album about called Seldom Seen Kid. I used to see Lemn Sissay a lot

A student-hating pub bore, Coogan explained that Calf was “based on those working-class men who slightly resented subsidised government grants, as we had then…hardworking taxpayers would be in the pub moaning a bit about why their tax was going on those poncey, middle class people in tights prancing around and dossing about and not really contributing meaningfully to society.” He paused. “I’ve got a lot of sympathy with that point of view, but it’s also quite blinkered.”

By the time of his graduation in the summer of 1988, after his final-year performance of Wall in A Midsummer Night’s Dream (he played Wall as Duncan Thickett), Coogan had made his first TV appearances, secured a role in Spitting Image, had an agent, and had even already enjoyed a small part in a feature film directed by Paul Greengrass.

Initially, Coogan stayed in Manchester, travelling weekly down to London to record Spitting Image and perform on London’s comedy circuit. Quickly, he spent more time in the capital, appearing on Sunday Night at the Palladium with national acclaim within reach.

By the early nineties, Paul Calf was a TV regular and he was soon to debut the Alan Partridge character as a bungling sports reporter in On The Hour. The rest is history.

Branching out

While the seeds of his success were sown while he was studying at Manchester Metropolitan, Coogan doesn’t attribute this to the course itself. “I was not particularly studious. My career blossoming stems from all the stuff I was doing when I was moonlighting from my course, doing stand-up and voiceovers out in the real world.”

However, while the course content wasn’t to Coogan’s taste, he did learn a lot from the practical skills he was taught. “The technical side of the course proved very useful later on, Alexander technique [posture exercises] and all the breathing and all that sort of technical theatre stuff was very good.

“The other stuff of how to act is so subjective it’s very difficult to teach any single correct way. They taught a Stanislavski-type methodical approach and I wasn’t very good at that. In the end I did something completely different. But all the technical stuff, the fencing and the yoga, the breathing definitely proved useful to me in my career later on. I am grateful for that.”

Coogan is most well-known for his comic acting, but more recently has won plaudits for performing and writing straight dramas. His work has tackled serious social and political issues, from Magdalene laundries in Philomena to the morality of extreme wealth in Greed.

In his autobiography, Coogan claims he never aspired to be a comedian – it was just the quickest route to getting an Equity card after graduating from Manchester School of Theatre. Now, he explained, he is restless to use his time and creative energies on projects that matter to him. “Comedy is one of the tools in your toolbox. And it’s a really good one, a very useful one. And if you know how to do it, it’s a great way to sugar the pill of a difficult subject matter. “[But] anything I do has to have some sort of substance to it…. that’s saying something about humanity. Otherwise, I just am too old.”

Seeking fresh talent

He is an outspoken voice on a number of issues too outside of his work, from phone hacking to inequality and elitism in the arts.

In his autobiography, Coogan described the apprehension he felt during his first round of auditions for London drama schools, as a lower middle-class boy from a Manchester suburb, among a coterie of privately educated applicants, many of whom seemed to already know the tutors. It is a fire that clearly still burns within him, three decades later.

He said: “Drama does tend to attract middle class people … but appears to me that in the 1960s and 70s moving through to the 80s, that the arts were an opportunity for people who were talented to break through normal class barriers.

“Then it struck me that as the decades rolled by, the more privileged sections of society thought that these professions were actually quite legitimate. And so the more privileged members of society started to get in on the whole acting profession, and consequently, while in the 1960s you had plays by working class writers, angry young men, probably a product of the grammar school system, the intellectually aspirant but very working class playwrights and actors, that seems to have disappeared.

“All we really have now is lots of upper middle-class actors and upper middle-class writers writing for each other. So we have this conceited circle of creativity, which I find slightly tedious.”

That may be one of the reasons why Coogan regularly seeks out new collaborators, most notably the Gibbons brothers who have worked on modern Partridge projects. He is drawn to originality, citing the example of Tim Key who first played Sidekick Simon in Mid Morning Matters with Alan Partridge.

“When I first saw Tim Key perform, I was excited because he was not derivative in any way. And he remains faithful to his own voice. He listens to himself and his own instincts when he performs.”

So how would a young Manchester School of Theatre performer catch the eye? He said: “The world is different now with social media and YouTube. [When I started] it was just ‘do a gig here, do a gig there’. You can be influenced by people – I’ve been inspired by lots of people, by all the populist comedy writers. I’m also inspired by the esoteric, slightly surreal comedy writers. [But] try and have your own voice, not just emulate the things that you like, but to think how you can do something different and something that feels original.”

Partridge returns

Partridge fans will be relieved that Coogan’s most enduring creation returns this year with This Time – with the Norwich-based DJ finally getting his second series on the BBC. He relishes reviving Partridge, not only because he enjoys slipping into Alan’s comfortable loafers, but because as a character he too fulfils a deeper purpose.

He explained: “You can do things that you can’t do with a new character because the audience who love it feel intimately connected with Alan. So you can be really nuanced and subtle with things and most of the audience will get it.

“It is like an alter ego. I can occupy his mind and mentality quite easily. Also it’s a way of exploring different kinds of comedy. You can do documentary things, apply the character to different things as a filter for the changing times and changing cultural observations.”

‘Follow your instincts’

The COVID-19 crisis has impacted the entire arts sector. Young drama students taking tentative early career steps are now coming to terms with a world entirely different to the one they were expecting.

Coogan’s tips for young actors and writers, issued before the pandemic, now look even more pertinent.

“The best advice to students is to follow your instincts,” he said. “What I’ve learned is … just because someone said this is the way you need to do something doesn’t mean you have to do it that way.

“Some sort of self-reliance [is important], it can be a bit debilitating if you’re just desperately waiting for someone else to give you a job.

Where I am now is exactly where I want to be.

“And flexibility. I went where the work was. I wasn’t especially interested in doing stand-up comedy on Sunday Night at the Palladium with Jimmy Tarbuck when I was 22, but it’s where the work was. Once you’re inside then you can manoeuvre and try and move sideways.”

In short, it’s a long career, and this current crisis won’t last forever. And while not every Manchester School of Theatre student will have as stratospheric a rise as Coogan, following his advice can only make it more likely that Manchester School of Theatre’s glittering roster of alumni continues to swell.

“I’ve spent my last 30 years trying to get where I am now,” said Coogan. “But where I am now is exactly where I want to be.”