Putting the pieces together

"We got a phone call to say that Sobhia had been murdered and found in the bathroom.

“This guy had got Sobhia wrapped up in this thing where he’d detached her from her family and friends and told her that nobody would come to her aid.”

The words of Sobhia Khan’s brother will be hauntingly familiar to many bereaved by domestic homicide. Sobhia was brutally murdered by her husband in May 2017 after months of psychological and physical abuse.

After he was given a 32-year prison sentence in 2018, an independent report identified multiple authorities’ missed opportunities and miscommunications in the years leading up to the murder.

“I look at my sister’s case and the agencies that were involved, and I think that if they’d acted on the information they knew, then Sobhia would still be here,” her brother said.

The communication between multiple agencies and organisations is a key factor in groundbreaking research from Manchester Met, which influences approaches to domestic abuse to prevent more cases such as Sobhia’s. The Homicide Abuse Learning Together (HALT) study is part of this research.

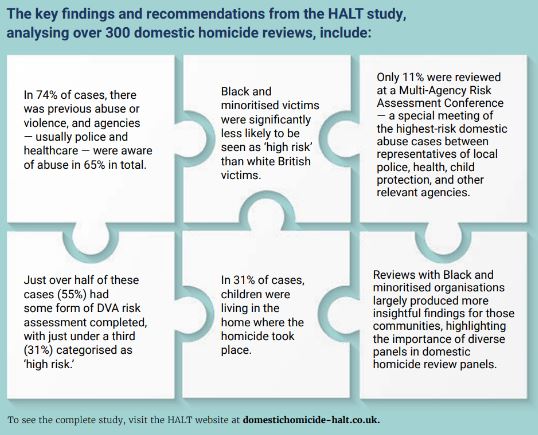

Led by Khatidja Chantler, Professor of Gender, Equalities and Communities at Manchester Met, the project analysed the findings and processes of 302 domestic homicide reviews (DHRs). It was the first large-scale national study of its kind since they were legally mandated in England and Wales

over a decade ago.

DHRs were established in 2011 to understand the experiences that lead to domestic homicides, the role of service responses in identifying missed intervention opportunities, and to make the victim visible.

“We first looked at DHRs on an international scale to learn more about the processes and to see what works so we could make recommendations for the UK,” says Professor Chantler.

“Because this is a relatively new form of review, which are publicly available, we wanted to find out more about what had happened before each homicide in terms of service engagement as well as what people knew about the victim and the perpetrator to see if there are any lessons that could be learned to prevent such instances happening in future.”

What has resulted from the study is the first repository of DHRs in England and a series of briefings and articles aimed at helping policymakers and service providers. Films have also been created based on the experiences of current victim-survivors of domestic abuse and family members who have been bereaved by domestic homicide, as well as an anthology of poems in conjunction with the Manchester Poetry Library at Manchester Met.

“The HALT study has generated new findings based on the type of domestic homicide and the age, gender and ethnicity of victims and perpetrators,” explained Prof Chantler.

“We wanted a human aspect to our research, so instead of only analysing domestic homicide reviews, we wanted to understand more about those who are current victim-survivors of domestic abuse and those who have been bereaved by domestic homicides.”

Professor Chantler and her team found that domestic homicide is predominantly carried out by men

against women. In fact, men were the perpetrators in 90% of the cases analysed. In nearly three-quarters (74%) of cases, there had been domestic violence and abuse in the victim-perpetrator relationship before the murder.

Other risks identified throughout DHRs include alcohol or drug misuse, economic and housing difficulties, and diagnosed mental health conditions.

“What we’ve found is that agencies in the areas of health, mental health and substance abuse are key organisations that need to engage with domestic abuse,” said Prof Chantler.

“However, what happens in cases in these areas is that agencies tend to focus purely on the symptoms and diagnoses of whatever the health issue may be instead of a more holistic form of assessment.

“We’ve highlighted the importance of effective multi-agency working, which is an issue that comes up time and time again in all kinds of reviews. We need to know what a good multi-agency model

looks like and how this can be tested and put into action.”

Which is exactly what the HALT study is doing. Its findings now influence the UK Home Office and

Domestic Abuse Commissioner’s Office approach as they shape their new policies and strategies.

The Domestic Abuse Commissioner’s Office is working with Professor Chantler to focus on specific service areas. These include adult and children’s social care, health and criminal justice to inform the domestic homicide oversight mechanism, identifying more ways to prevent domestic homicides.

Domestic Abuse Commissioner Nicole Jacobs said: “Too often, we see the same recommendations made but not implemented at a national level. Our oversight mechanism will provide the means to draw out themes and trends in those recommendations to make sure that lessons are learnt and future deaths are prevented.

“We must improve the system of DHRs so that we can see meaningful change for victims of domestic

abuse and their families and highlight those areas that are most in need of improvement.”

A vital factor in shaping these plans is the new information brought to light by the HALT study on the different types and contexts of domestic homicide. Examples include adult family homicide in family members over 16 years old who are not in an intimate relationship, as well as analyses of homicide-suicides.

The study also analysed domestic homicides involving female perpetrators and those involving Black and minoritised victims or perpetrators.

“Our understandings are continually changing around what constitutes domestic abuse,” explained Prof Chantler. “For example, it is only relatively recently that coercive and controlling behaviour is specifically mentioned in the law as a form of abuse. For our understanding to develop, it is crucial that research is taking place to evidence and highlight different forms of domestic abuse, as well as how domestic abuse impacts the UK’s diverse cultures and communities.”

Researchers have stressed the importance of support for families with children — through social services, schools and other agencies. However, the same opportunities for experts to identify and flag domestic abuse do not exist for adults in abusive relationships where children are not present.

“This is providing us with a more nuanced understanding of domestic homicides,” said Prof Chantler. “And that will inform the work of the multiple agencies who can help to prevent such tragic cases.”

For Professor Chantler and her team, this involves engaging with local agencies, including Greater Manchester Police, local authorities, Manchester Women’s Aid and other charities.

“It is crucial we get these types of organisations involved in the conversation and bring them together to develop a multi-agency framework that is robust and establishes ways of working for the future,” said Prof Chantler.

While the work continues to turn the findings from the HALT study into meaningful action that impacts people across the country, for the people left bereaved by domestic homicides, the research has highlighted their conclusions that there is a need for improvement in the way DHRs happen.

Sobhia Khan’s brother is clear when he told researchers during the project how his family had felt let down by the process.

“A domestic homicide review is supposed to be something you can learn from,” he said, “But I question how many reviews have happened from when they were first introduced up until now [and] whether anything has been learnt.”